Here is what you may want to know about it

Many Italian surnames coincide with a place name – a nation, a region, city, town, village or hamlet – and the reasons may be different, sometimes even surprising.

In this post I will try to answer your questions about it, for example:

- If my ancestor’s surname is also a place name, does this mean that he was coming from that place?

- Was the place named after my family, or the opposite?

Disclaimer: this is not the result of a specific study, it’s only the consequence of my experience “on the field” and so, my approach will be very practical.

If you are from America, Canada or Australia, you are very used to surnames which are also place names, as there are many examples in your Countries, such as Washington, Vancouver and Sydney.

In these three cases, and in most cases in your Countries, a new city was named after a famous person, as a tribute.

This is situation is very rare in Italy and the reason is simple: most cities and towns, villages and rivers, mountains and gulfs were named long before people started to have surnames!

THE ORIGIN OF SURNAMES

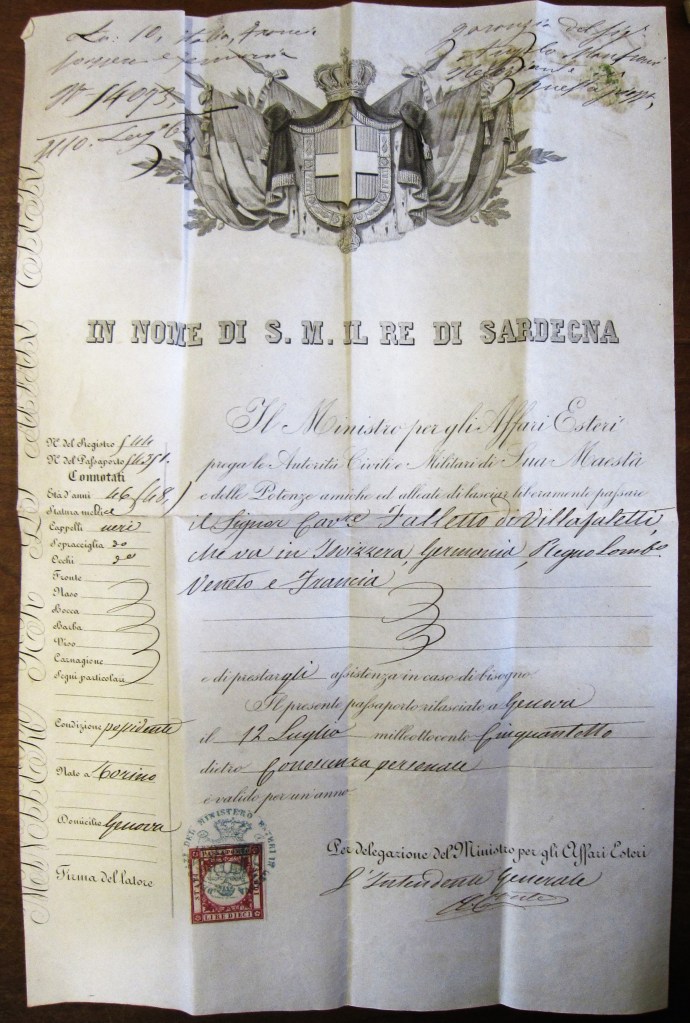

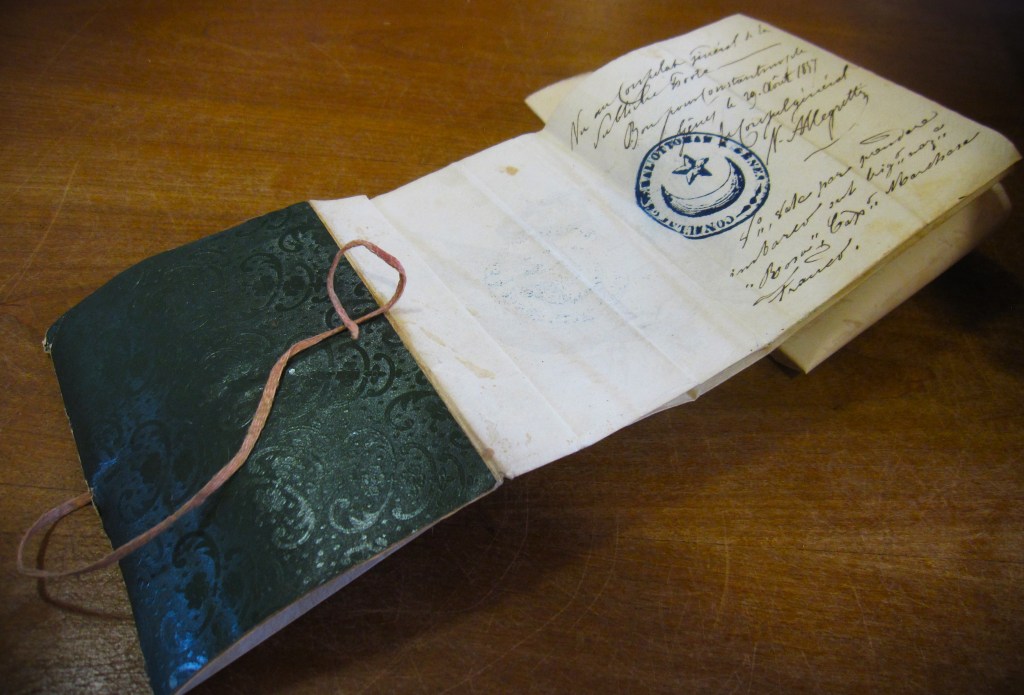

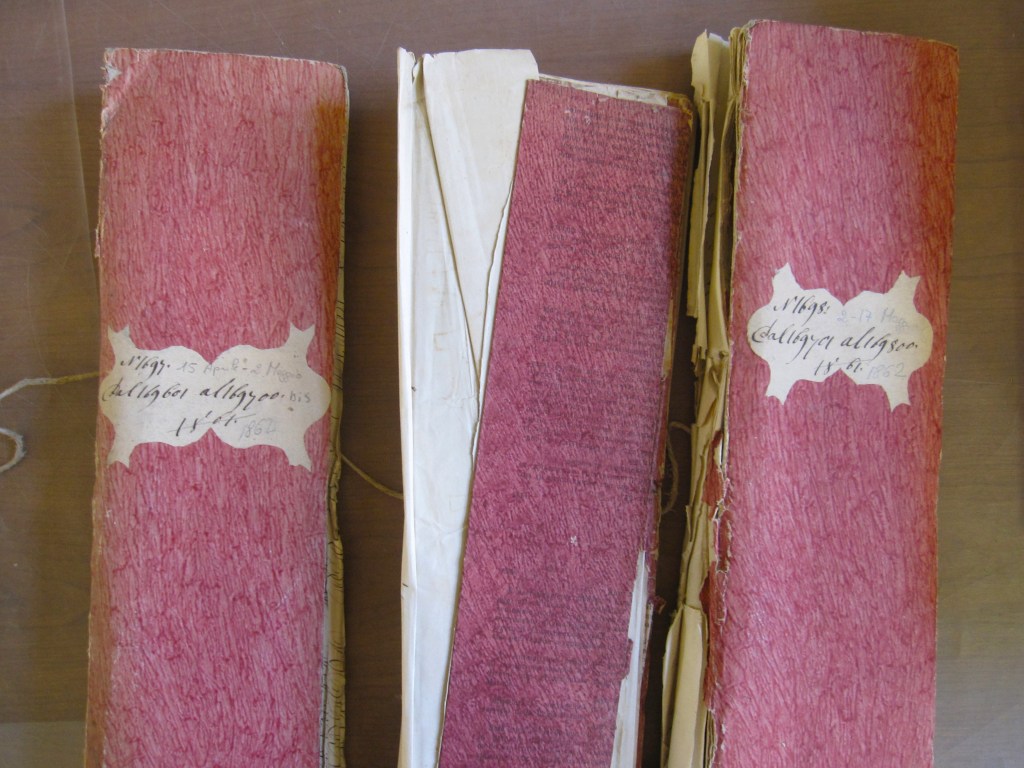

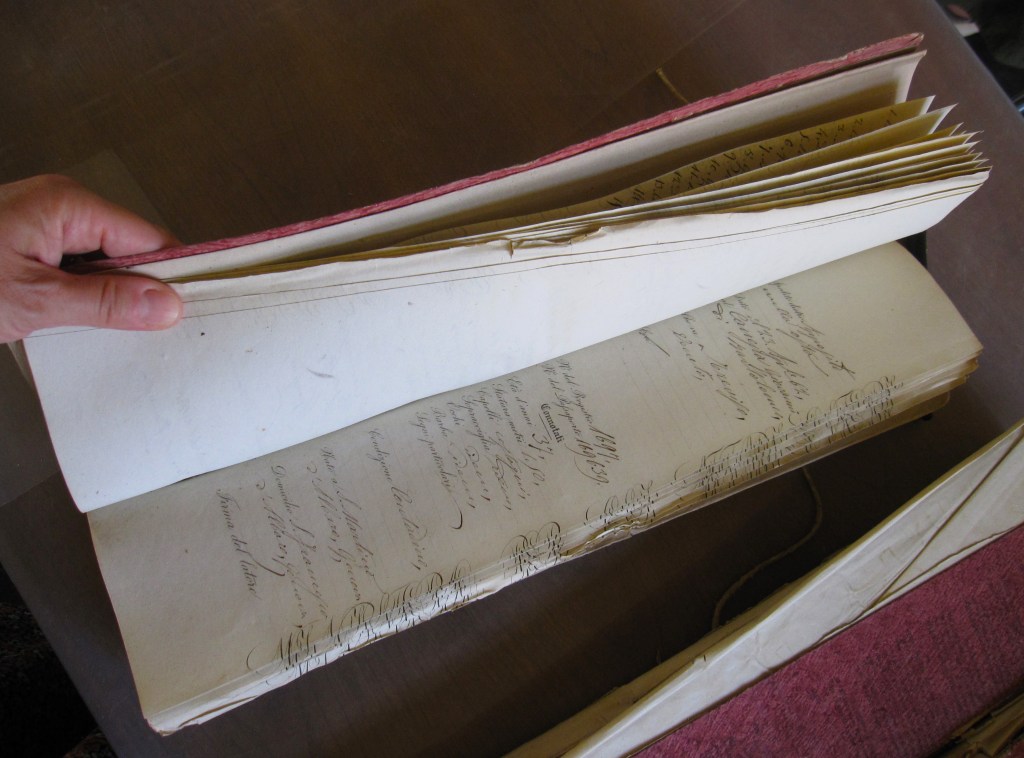

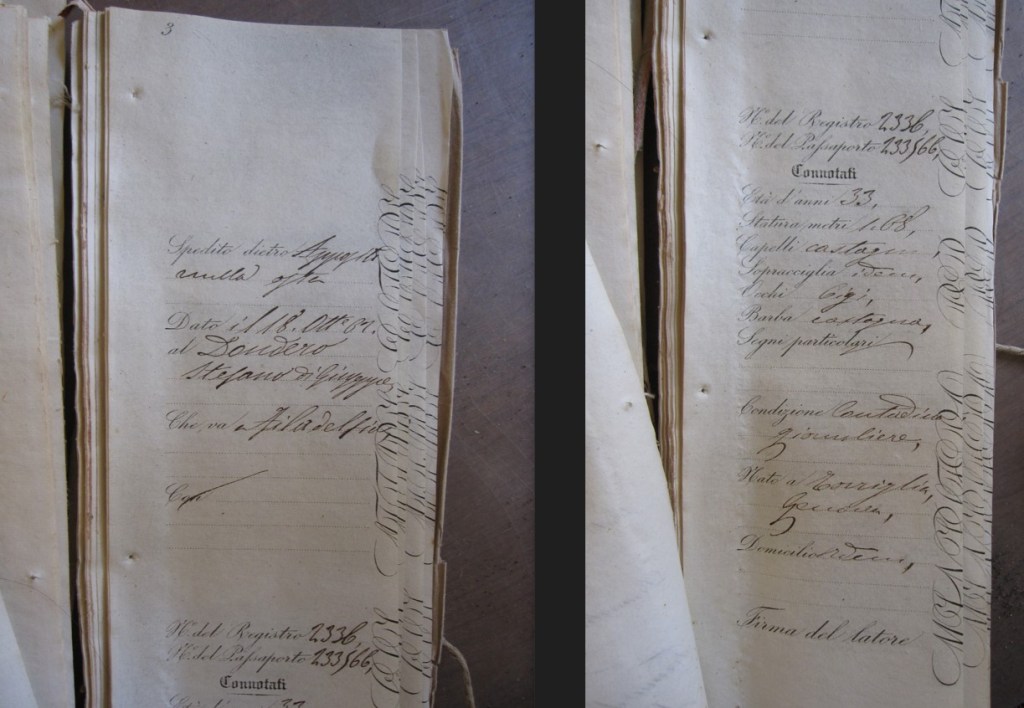

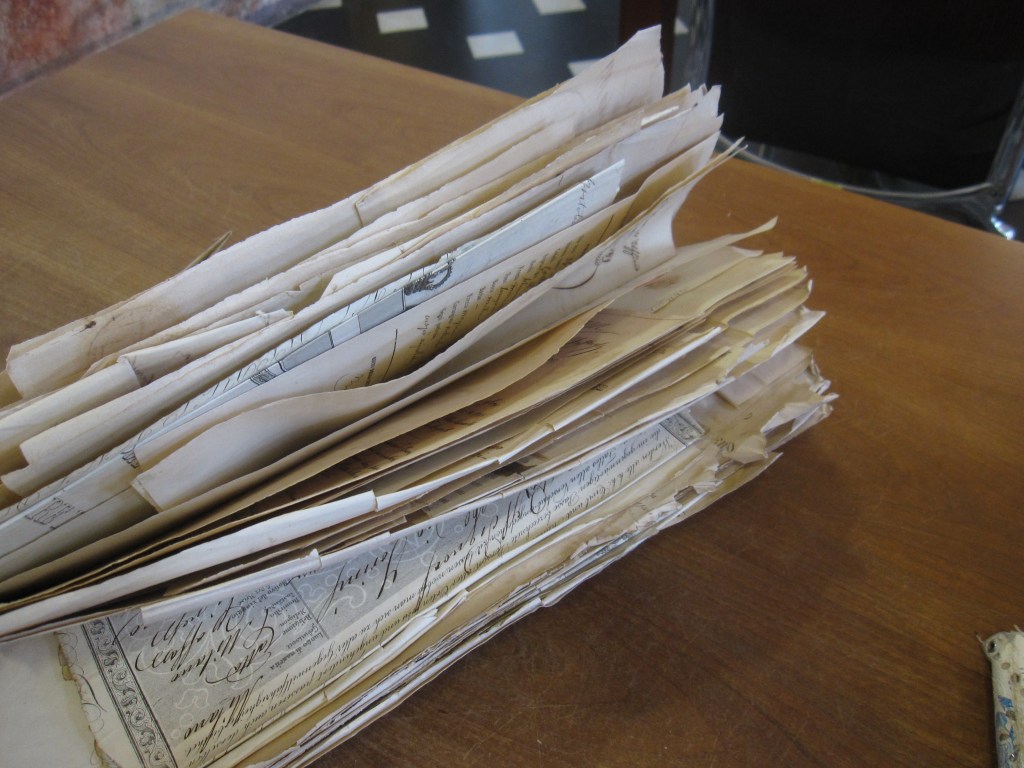

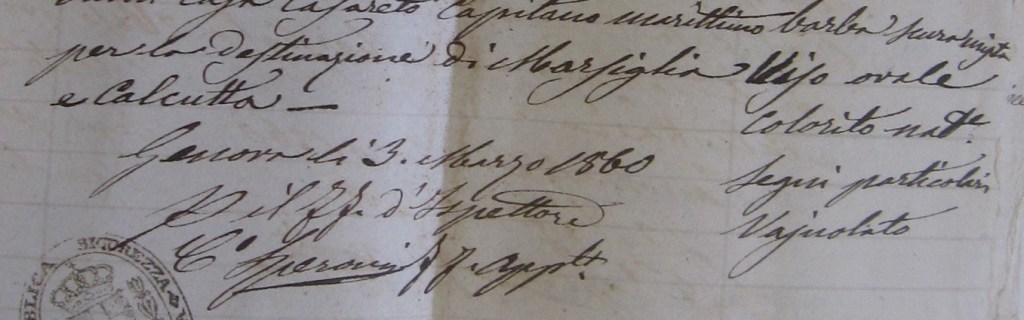

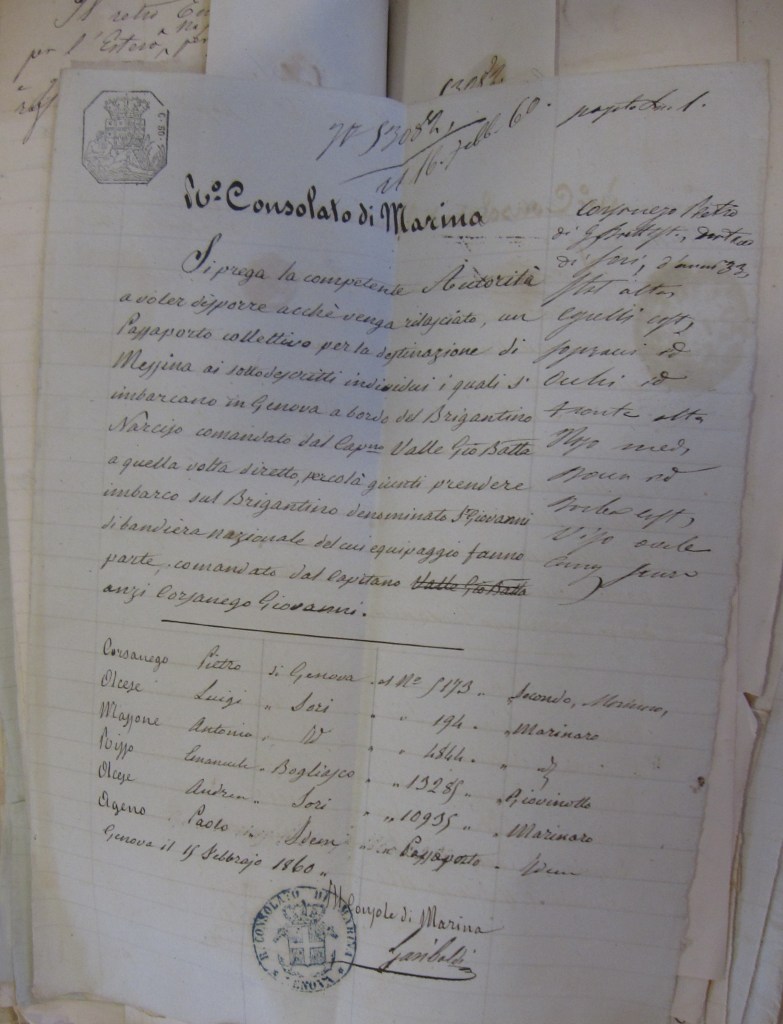

Let’s make it quick and simple: surnames started to be used in the late Middle Age, but they were officialized only at the end of the century 1500, adopting as surname the nickname a person was known with, which could be his job, the name of his father, a physical characteristic, his place of origin or something else (there may be many examples).

Here are the categories that I identified, referring to surnames which are also place names.

PEOPLE NAMED AFTER THEIR PLACE OF ORIGIN

The majority of people whose surname is also a place name, may be native of that place.

However, this means that they were living in that place before the introduction of surnames, many centuries ago!

For example, if in the Middle Age a family was moving from Monza to another place (let’s say Milan), they were identified as “those from Monza”, and when surnames were formally introduced, it is possible that they adopted the surname Monza, because this is how they were known in Milan.

This means that you will never find traces of your Monza family in Monza, because they were called Monza only after leaving this city and settling in another one.

Besides this, the adoption of the surname Monza may have happened before the introduction of parish records, and it may be very difficult or even impossible to get to the origins of it.

The above example is a good one, actually.

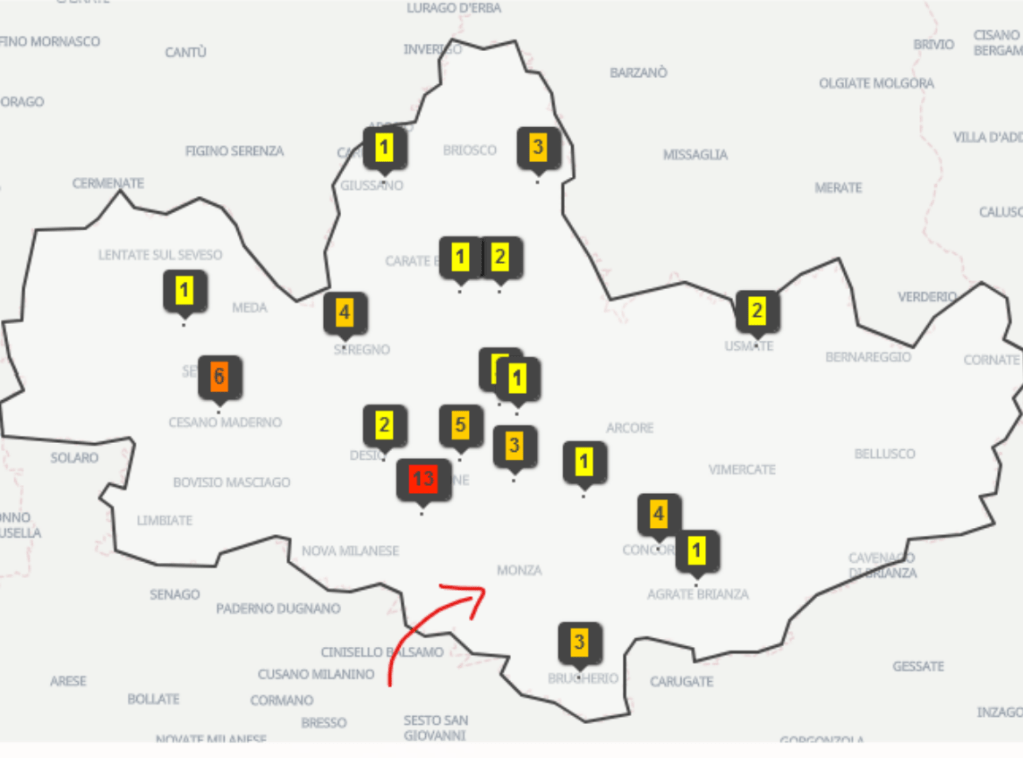

There are, in Italy, 495 families with surname Monza

Guess how many are living in Monza? No one!

Of course, because Monza was the surname which was given to people whose distinguishing characteristic was that they were coming from Monza, but there was no reason for a person living in Monza to get the nickname or surname Monza, as it was not a distinguishing mark.

(Source: https://www.cognomix.it/mappe-dei-cognomi-italiani/MONZA, accessed January 25th, 2025)

This is true also for surnames which are adjectives instead of nouns, such as Lombardi, Siciliano, Napolitano, Spagnoli (from Lombardy, Sicily, Naples or Spain respectively).

If your ancestor’s surname is GALLO or GALLI, you are in the same group, too!

Gallo has two translations: one is rooster, which is not the meaning of the surname, the other one is Gaul, thus French: your ancestors were then French people who settled in Italy some time in the distant past.

PLACES NAMED AFTER THE PEOPLE WHO WERE LIVING THERE

So, if your surname is Roma, I am sorry if you are disappointed to discover that the city was not called after you family!

On the other hand, if your ancestors were coming from a small hamlet, the place may actually have been called after them!

Imagine a small rural Italian town, a few centuries ago. Outside the town center, scattered in the countryside, are a handful of poor farmhouses, inhabited by families of farmers.

How do you call those places? Of course, like the people who are living there!

How can you recognize if the place took its name from the family, or if it’s the family who was named after the place because it was their place of origin?

Here is a very practical way (not 100% sure, but almost): check if there are still families living in that place, with that surname!

Here is an example: Cimelli is a surname and also the name of the hamlet of a town in Emilia Romagna. There were – and still are – families with the surname Cimelli living in Cimelli, so their surname cannot be a distinguishing mark, it did not suggest that they were “coming from Cimelli”.

For this reason, it is very likely that the place was named after the people who were living there.

Another example is even clearer: it’s another minuscule hamlet of a tiny town in Piedmont, and its name is Delaurenti, which means “(son) of Lorenzo”.

It is obviously a surname, a patronymic, not a place name. It was called after the family who was living there, whose surname was Delaurenti.

PLACES NAMED AS A TRIBUTE

So, a person named after a place, to indicate the origin, or a place named after a person to indicate the residence… No tributes like for Washington?

Most places in Italy had already their names when people did not have surnames yet, so how could they be re-named to honor a famous person?

In a few cases they did, adding their important citizen’s surname to the town’s name. Here are a few examples:

- Castelnuovo Nigra, in Piedmont, renamed adding the surname of its famous citizen Costantino Nigra (poet and politician)

- Andorno Micca, in Piedmont, renamed to honor Pietro Micca, a war hero who died in 1706

- Camnago Volta, a hamlet of Como where the famous chemist and physicist Alessandro Volta had lived

In these cases, if your family surname matches with that of the tributed person, your ancestors may actually be native of that town, and possibly also related with the famous person!

PEOPLE NAMED AFTER A RANDOM PLACE

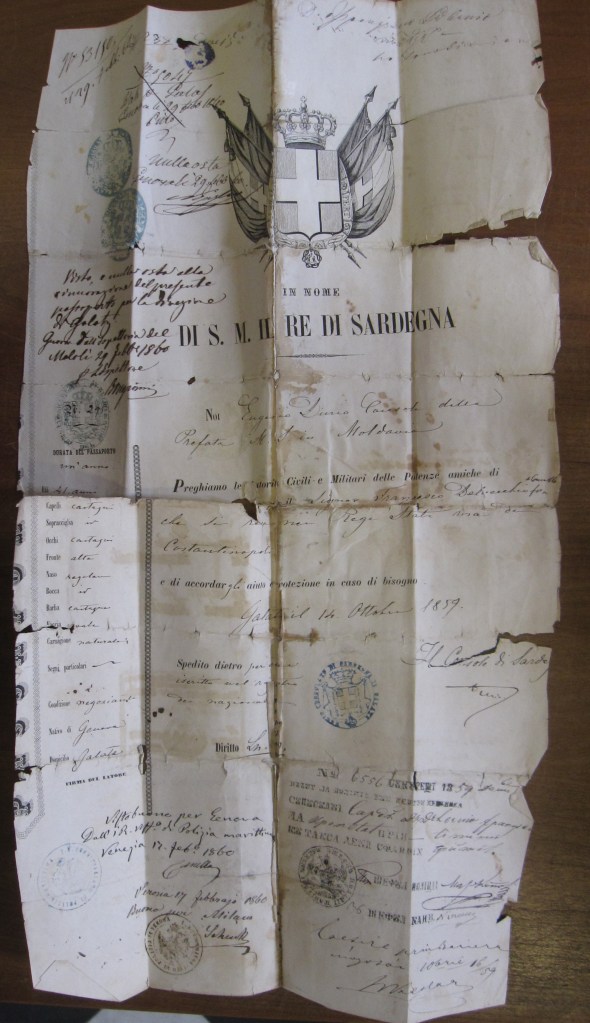

What about Rosa Teodosionopoli from Pellegrino Parmense?

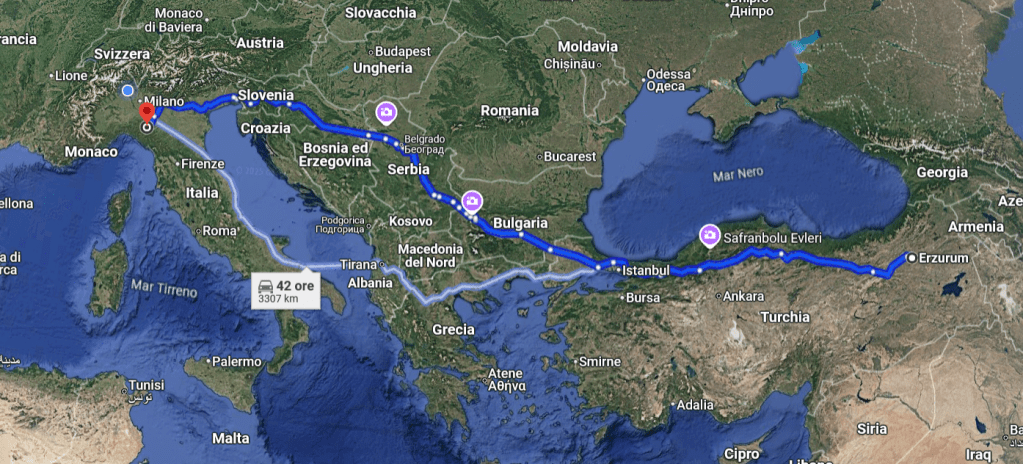

Teodosionopoli (Teodosiopoli, actually) is the ancient name of a city in Anatolia, Turkey, whose modern name is Erzurum.

Which amazing family history is hidden behind the surname of this person?

Were her ancestors actually born in the exotic city of Teodosiopoli?

Of course not. No historical circumstance would ever explain why a migrant from Teodosiopoli ended up in Pellegrino Parmense, in Emilia Romagna, but even if it would, the migrant would have been probably nicknamed Turco: Turkish.

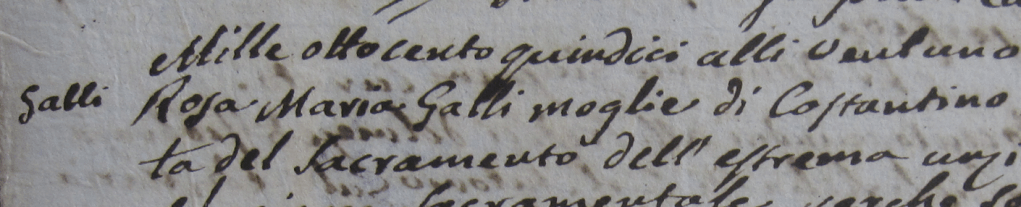

No wonderful family history for Rosa, unfortunately: she was a foundling, and this is the explanation of her surname.

When foundlings were abandoned at a hospital, they were given a random name and surname. In many cases, the inspiration for the surname was coming from a dictionary or encyclopedia, and toponyms were often used.

How to spot if a surname indicates the real origin of the family or if it’s an invented surname?

One way could be to analyze how far are the two places: the birth place and the place name used as surname.

If the origin of the family was from a very small village in Calabria who migrated to a distant region, the nickname would have probably been Calabrese, which was enough to identify the family.

If the surname points at a small town which is very far from the birthplace, it is probably not related to the place of origin.

If the surname is an exotic place name such as Acapulco, it is surely the surname of a foundling.

If the surname is not very spread out in the area, and it looks like your family is the only one family with that surname, it is probably so, and your ancestor was a foundling.

I hope you found this post useful to the discovery of your family history!

Feel free to send comments or questions!