(All I discovered about them)

This post will hopefully reply to some of your questions about Italian passports, and if it won’t I hope it will be an interesting read, at least.

In the next chapters I will share with you everything I discovered about these important documents during my research at the Genova State Archive: I will tell you how they looked like, how they were obtained, which info were reported and also if a passport research is possible.

Let’s start discovering them!

A NECESSARY PREAMBLE

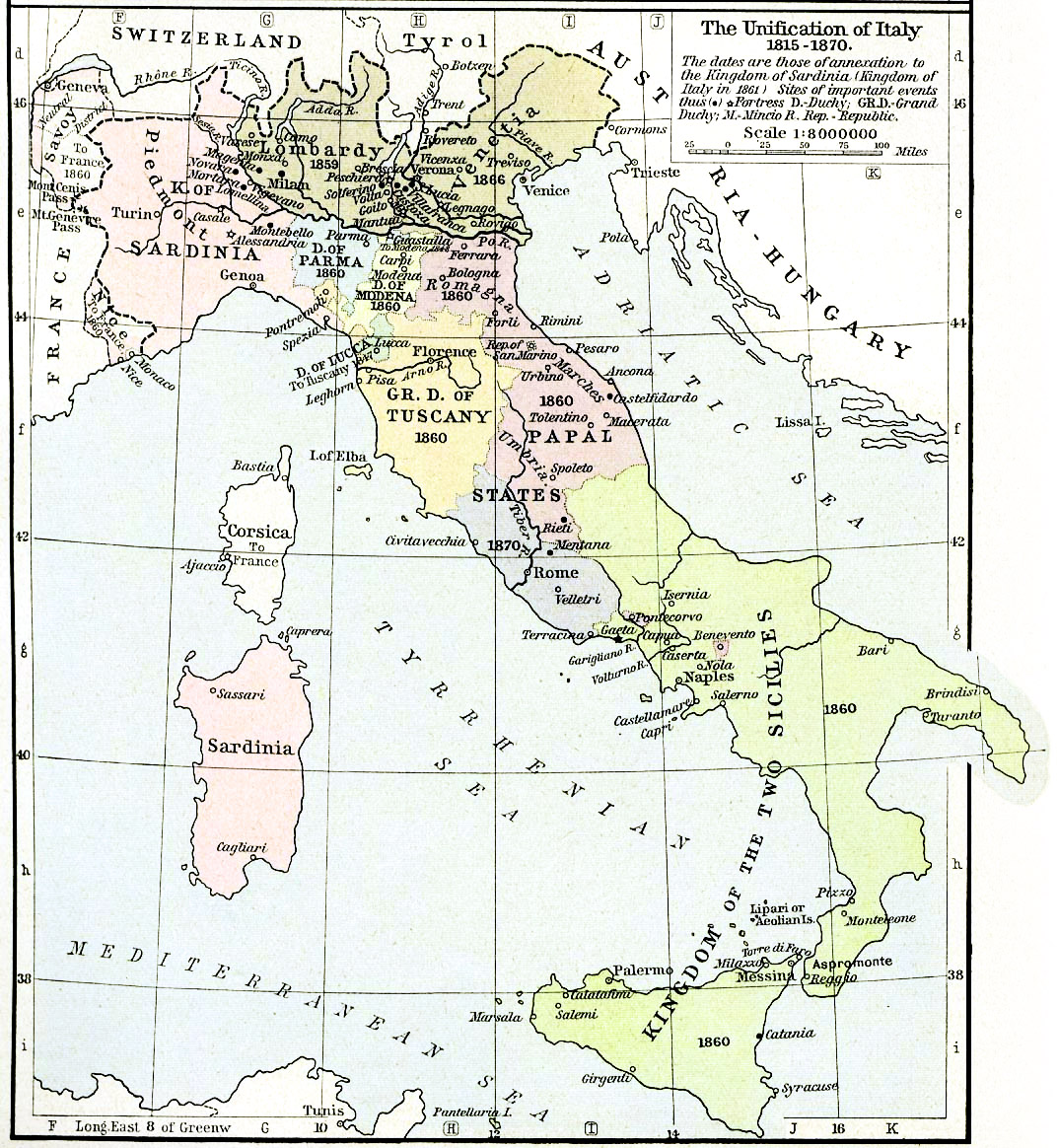

The Italian Nation was born on the 17th of March 1861, which is the date when the new Kingdom of Italy was proclamed, following the unification of the country as a consequence of our Independence Wars.

Before that date, the Italian peninsula was politically split in many different States.

The map above shows the different States just before their unification into the Kingdom of Italy.

Just to make it simple, here is an approximate conversion table.

| Present region/province | Ancient State |

| Piedmont, Valle d’Aosta, Liguria, Sardinia, part of south/west Lombardy, part of southern France along the coast, French region Savoy | Kingdom of Sardinia |

| Lombardy, Veneto, Trentino Alto Adige, Friuli Venezia Giulia | Lombardian-Venetian Kingdom governed by the Austro-Hungarian Empire |

| Provinces of Parma and Piacenza (present Emilia Romagna) | Duchy of Parma |

| Province of Modena (present Emilia Romagna) | Duchy of Modena |

| Province of Bologna, region Romagna, Marche, Umbria, Lazio | Papal States |

| Province of Lucca (present Tuscany) | Duchy of Lucca |

| Rest of Tuscany | Granduchy of Tuscany |

| All the remaining territory in Central and South Italy | Kingdom of the Two Sicilies |

Veneto and Friuli merged with the Italian Kingdom later (1866-1870), and there were mini-states that I did not mention, but it is not the scope of this article to get into these details. If you wish, you can check this Wikipedia page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_historical_states_of_Italy

What I wanted to highlight is that if your ancestor emigrated before 1861, he did not have an Italian passport!

His passport was emitted by one of the States listed above.

The other important detail to remark is that before 1861, people needed a passport to travel to the other States. Persons travelling from Milan to Genova needed a passport, as well as from Tuscany to Rome, or from Bologna to Naples.

HOW A PASSPORT LOOKED LIKE

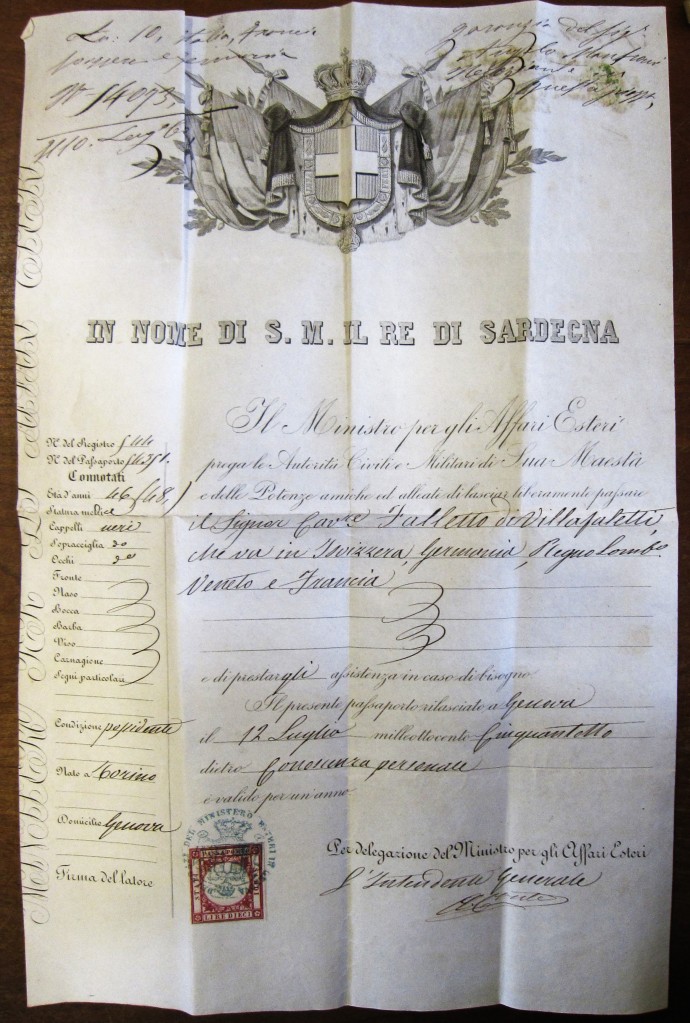

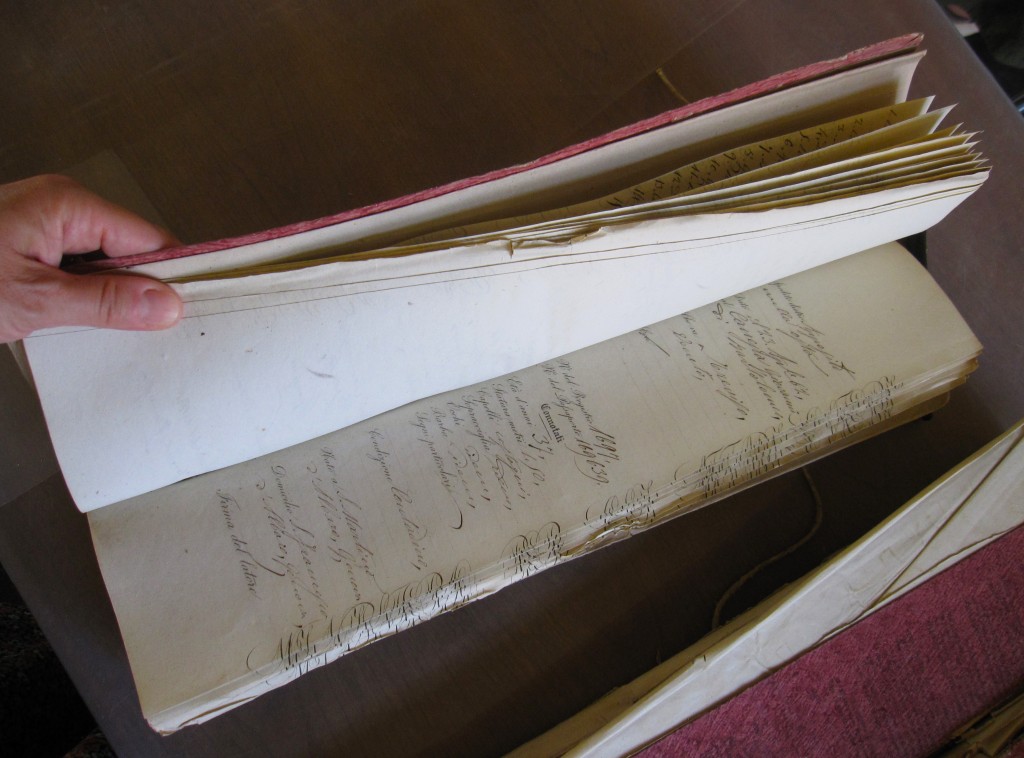

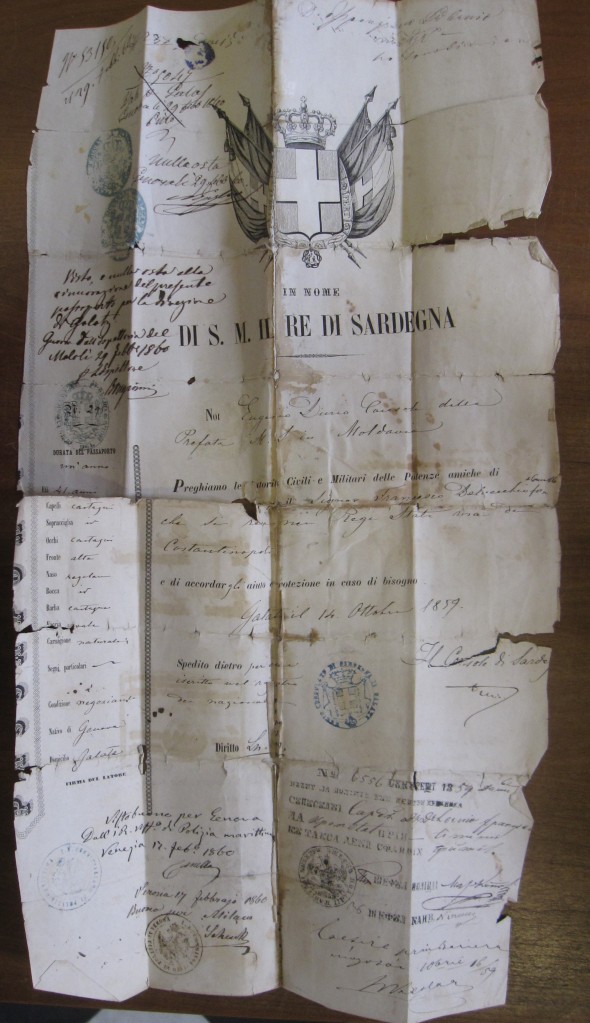

Forget the modern booklets with a hard cover and multiple pages, here is how a 19th century passport looked like

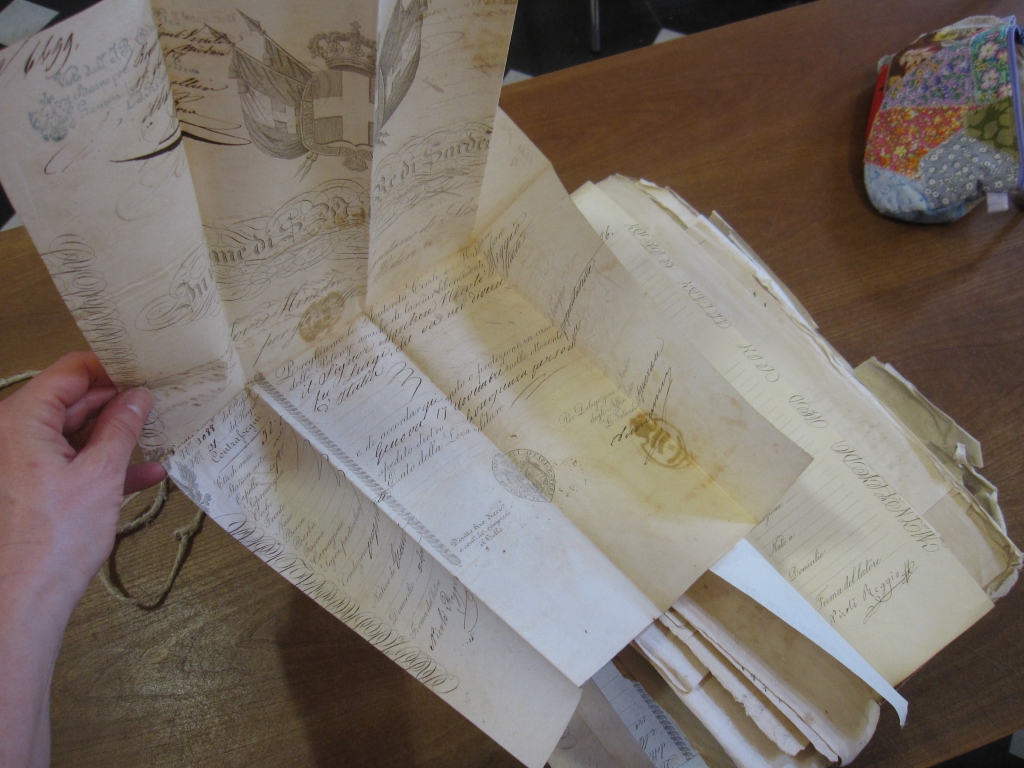

It was a single big sheet (bigger than a Letter format) and it was supposed to be folded the size of a pocket.

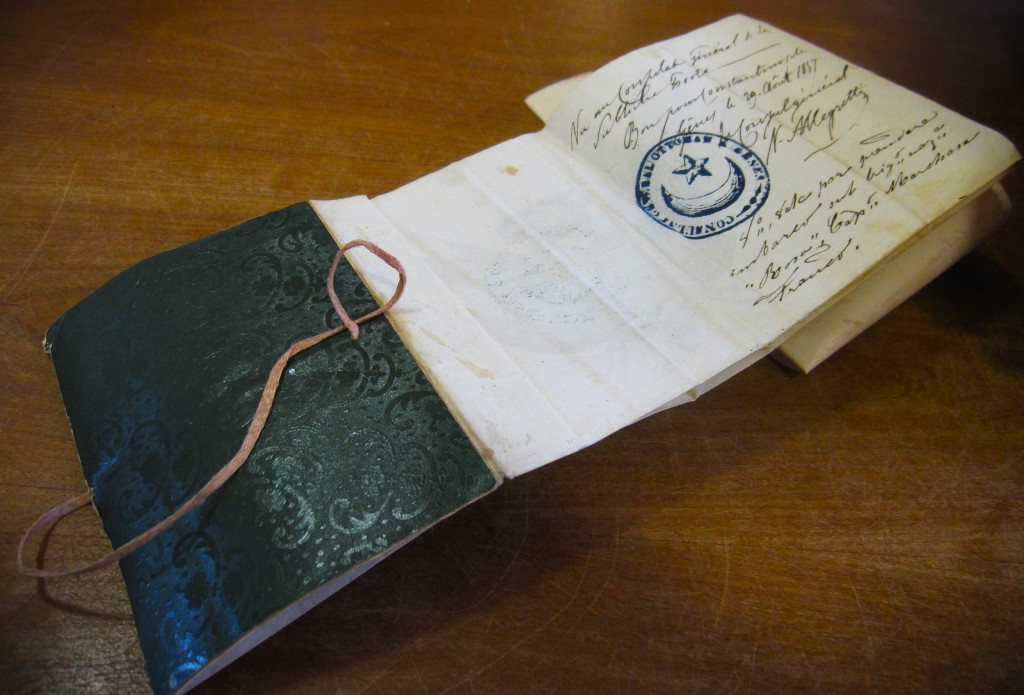

I also found an example that still carried part of a cover and the ribbon that was closing it

WHICH INFO IT REPORTED

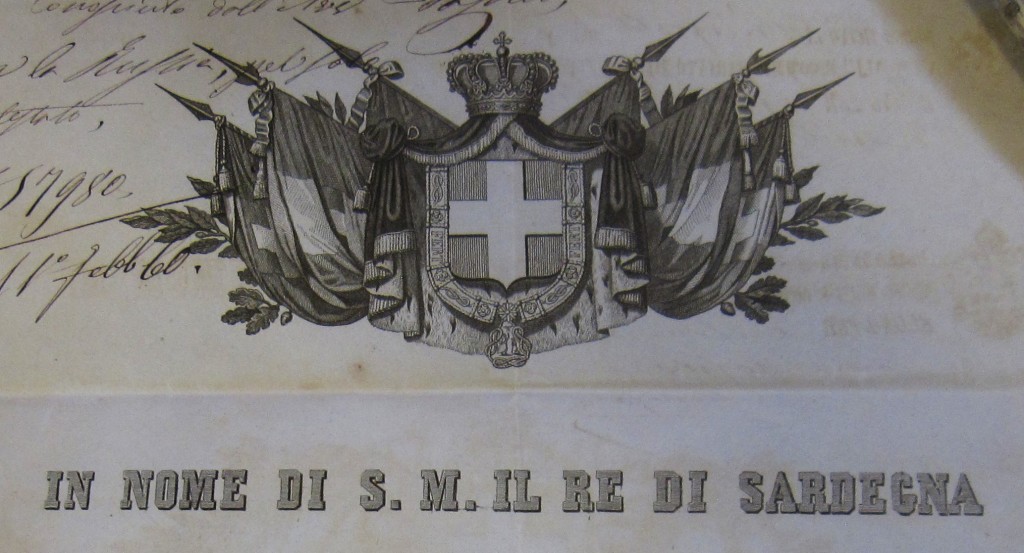

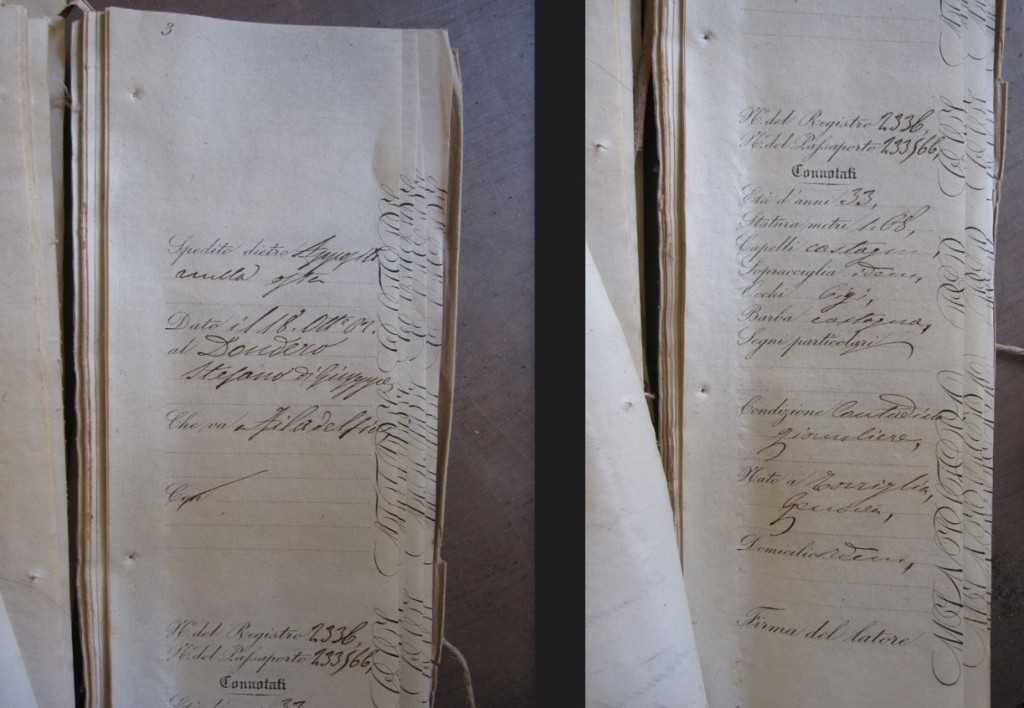

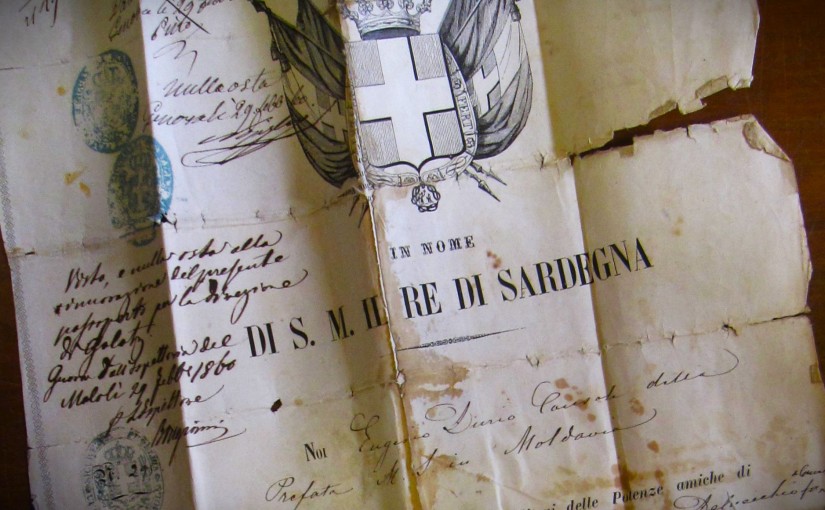

The passport carried, on its top third, a grandiloquent crest and introduction.

In this example, the writing in big letters declares “in the name of His Majesty the King of Sardinia”: it was 1858 and Italy was not yet unified.

The central part reported the name of the passport holder and the destination.

In the example above: Sir Falletto from Villafalletti, who was going to travel to Switzerland, Germany, Lombardian-Venetian Kingdom and France.

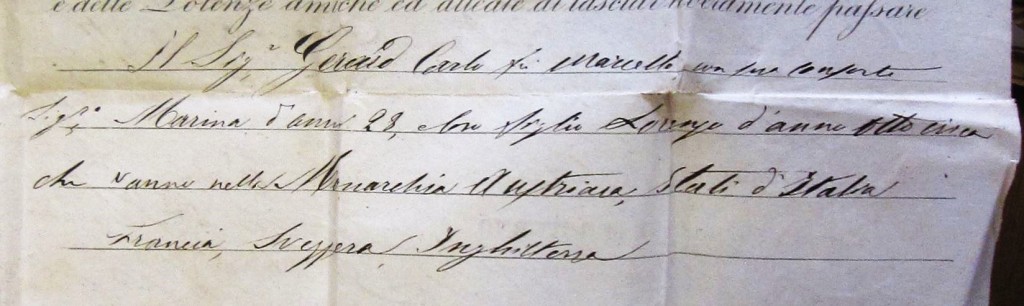

Here below another example where the passport was extended to the entire family: “Carlo Gerardo son of the late Marcello with his wife Marina aged 28 and their children Lorenzo aged 8”.

They were travelling to Austria, Italian States, France, Switzerland and England.

The bottom part reported the place and date of the passport emission and the documents that were provided to obtain a passport.

More about the required documents in the next chapter.

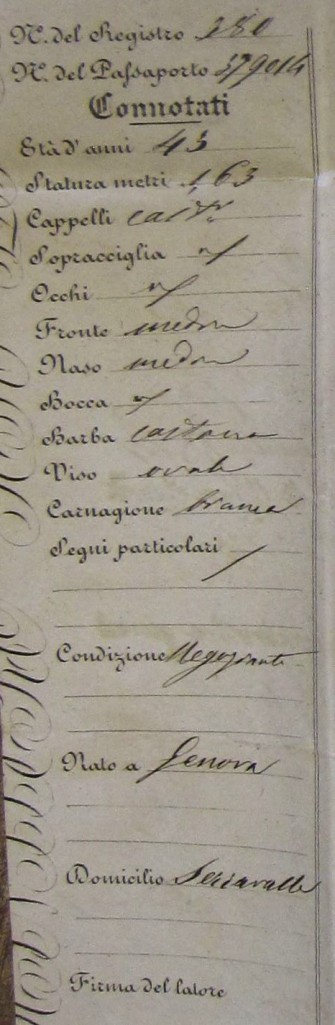

The left part is dedicated to the “photo” of the title holder. Of course, photos were not in use in 1858 and so, this margin is for the physical description.

The details which are reported are: age, height, hair color, eyebrows, eyes, forehead, nose, mouth, beard, face shape, skin tan, distinguishing marks.

The word “Condizione” meant profession: in this example, the title holder was a merchant, which makes the request for a passport plausible.

At last: birth place and domicile.

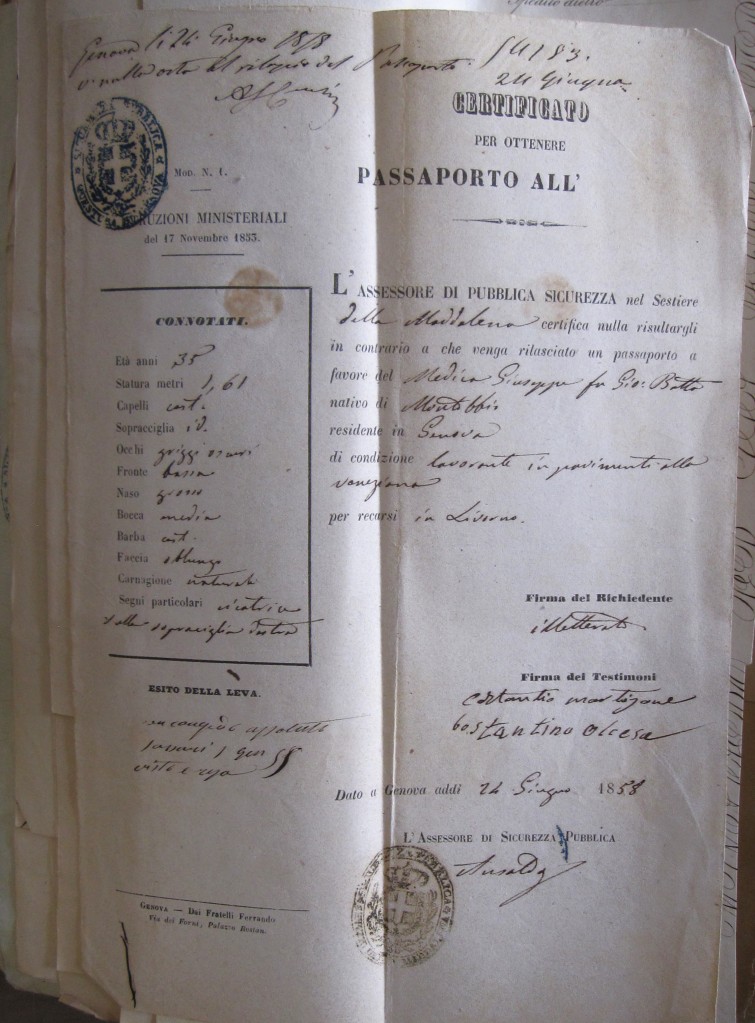

HOW A PASSPORT WAS OBTAINED

The passport was issued by the Questura, the central police station, on behalf of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Usually, it was necessary to show a “Nulla Osta” (no impediment), which was issued by the local Assessor to the Public Safety (Assessore di Pubblica Sicurezza). In this document, the Assessor declared that he was not aware of any obstacle that would prevent the applicant to obtain a passport.

For men, a note was added about their military status, whether they had served in the army. This was, of course, to avoid draft evaders to flee abroad.

In Genova, I had the chance to browse throught a few hundreds documents to request passports and I realized that, despite being the Nulla Osta the standard certificate needed for this request, in many cases alternative documents were provided: for clergy people, a reference letter from their superior was the rule; in one case, a woman obtained a passport by showing a heartfelt invitation letter from her husband to join him in America; foreign people who had been living in Genova for a while obtained a passport by giving back their expired, foreign passport (or at least, this is how I understood it).

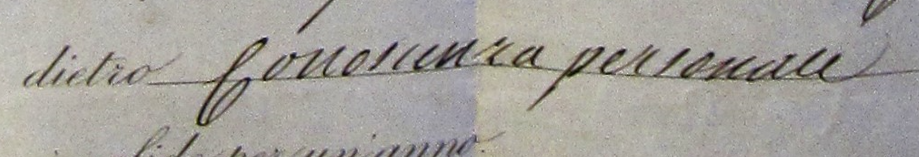

In the first example, Sir Falletto from Villafalletti was eventually a privileged: he did not provide any document or Nulla Osta and he obtained the wished passport because he was “personally known”.

HOW IT WORKED

The logic behind 19th century passports was different from today’s. In a way, they were more similar to a visa because they listed the places where the holder had in plan to travel, and also because they had a very short validity: 1 year.

Theoretically, the owner of a passport had to give it back to the Questura at his return from the travel mentioned in the passport.

Of course, this was not always done, especially if the passport was used to emigrate steadily and never come back.

IS PASSPORT RESEARCH AN OPTION?

The answer is in the few lines above: people who emigrated and did not come back to Italy, did not return their passport to the Italian Questura.

And also, as I said above: the passport was a single sheet of paper.

No copies, no duplicates.

If your ancestors emigrated overseas, the most probable place where the only one example of their passports can be is a drawer in an old relative’s house… if it’s still existing!

There are no copies in Italy, unfortunately.

So, what did I search, in Genova, exactly?

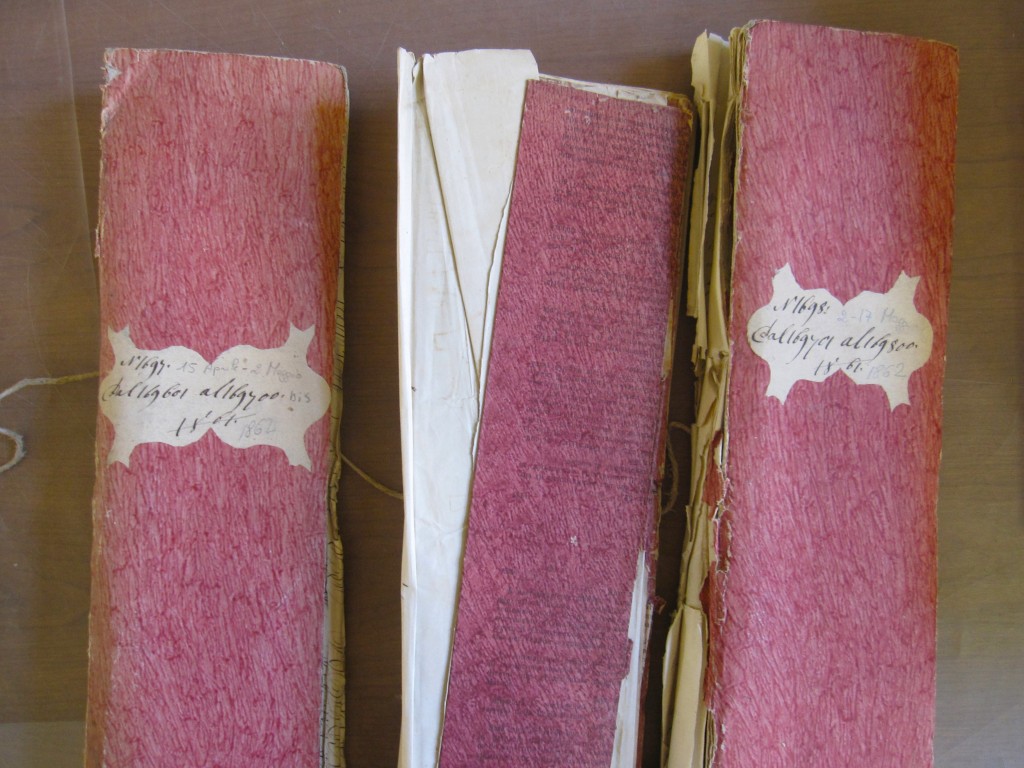

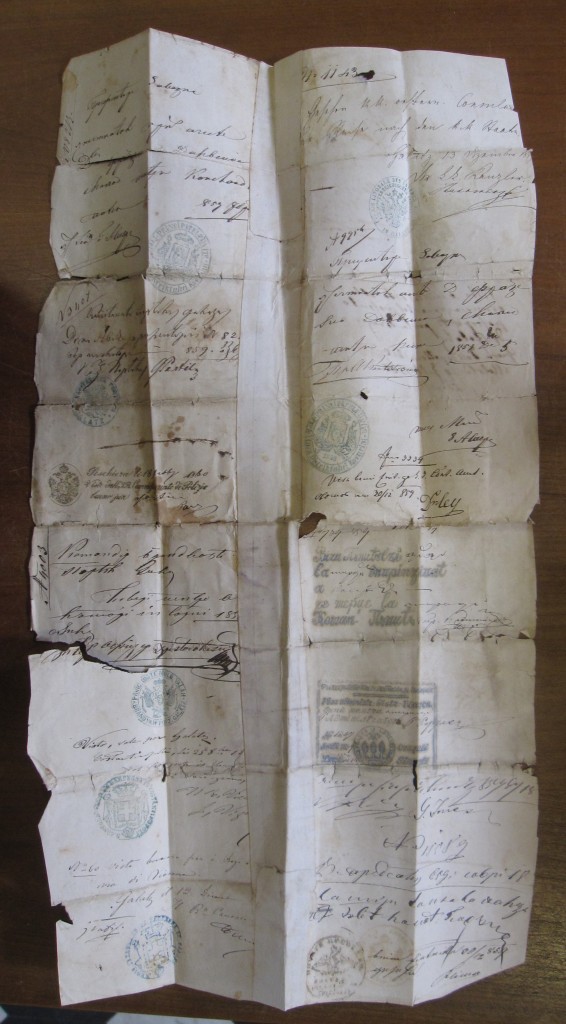

The Genova State Archive stores a collection called “Matrici dei Passaporti 1858-1873”: passport stubs from the year 1858 to 1873.

The time lapse is very limited, only 15 years, but every year contains the traces of approximately 1200-1500 passports! So it’s a big number anyway.

As just seen, the passport was a single big sheet. These sheets were bound in a register which contained 100 passports each.

For each sheet, the stripe that was along the binding of the register was the stub of the correspondent passport, which had to be compiled with the same data.

So, although it is very unlikely to find the real passport, it may be possible to find the stub reporting all the info, including the birth town, which is sometimes a brick wall to tear down.

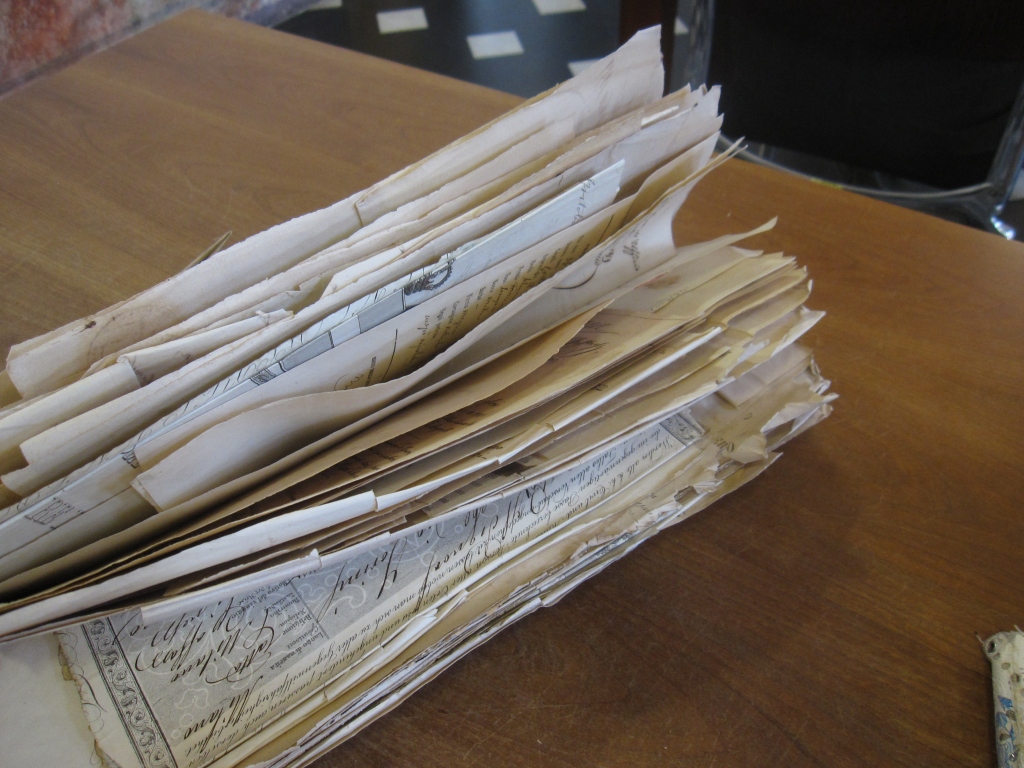

The oldest registers were organized in a different way: instead of compiling the stub, the Questura Officer was attaching the documents supplied to obtain the passport, hence the Nulla Osta or the reference letter, or even an old passport.

Browsing through this miscellaneous collection always opens up to surprises: if you find the document about your ancestor, you may discover where he was travelling to, when, and for which reason. You may discover other family members he was traveling with, or sometimes info about his military service such as the place where he served the army and which gave the authorization for the passport.

From a researcher’s point of view, it is hard job but very interesting.

So, if finding your ancestor’s passport may be just as probable as being hit by a meteorite while jogging in the park, the chances of stumbling upon a Nulla Osta, a passport stub or another document are much higher.

Here are some amazing examples.

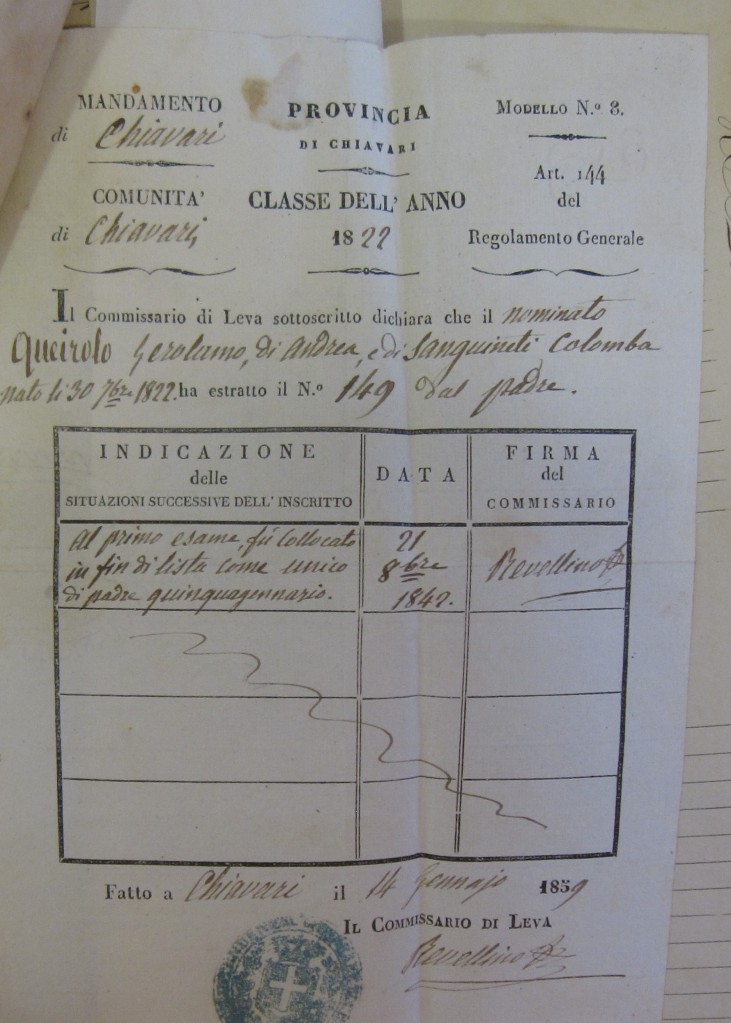

Together with the Nulla Osta, this man had to prove that he had accomplished to this military duties and he provided therefore a certificate stating that he was exempted by his military service for being the only son of a man older that 50: additional info that you would never expect to find in a passport collection!

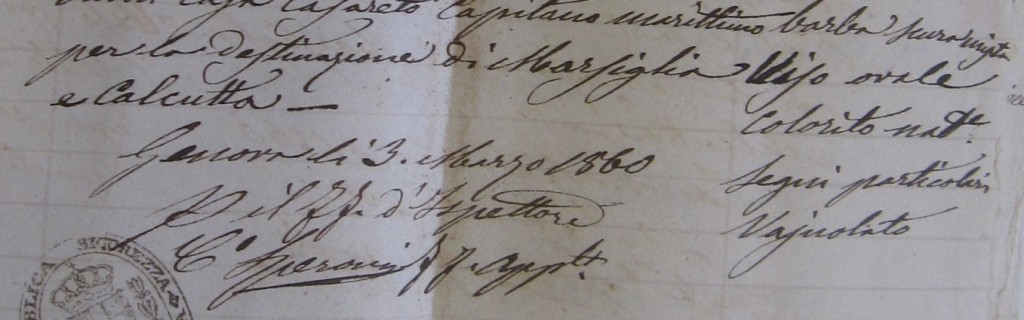

This is a crop of a nulla osta that I found by chance: he was the ancestor of another customer of mine, not the one who hired me to search for passports. I stumbled upon him and I was very surprised to discover that he was going to Marseille and Calcutta, because we only knew that he was a sea captain going back and forth Italy and South America.

Besides this, a note about distinguishing marks revealed that he was “vajuolato”, hence that he had had smallpox and survived, but his face showed the typical smallpox scars.

I never expected to find such detailed info about an ancestor!

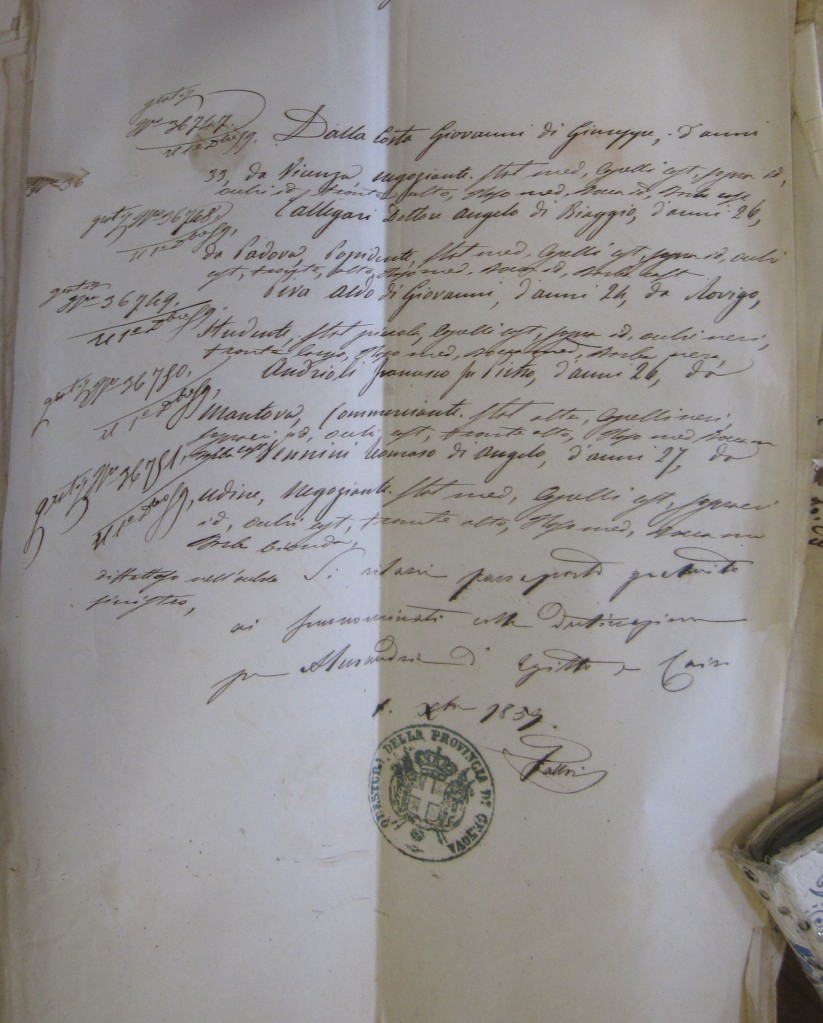

This was the authorization to issue 5 passports to people who were not from the Kingdom of Sardinia: I think that they were in transit, heading to their final destination Alessandria, in Egypt, but eventually they needed to have a passport, and the Questura of Genova issued it.

They were a merchant from Vicenza, an owner from Padova, a student from Rovigo, a trader from Cremona and another merchant from Udine

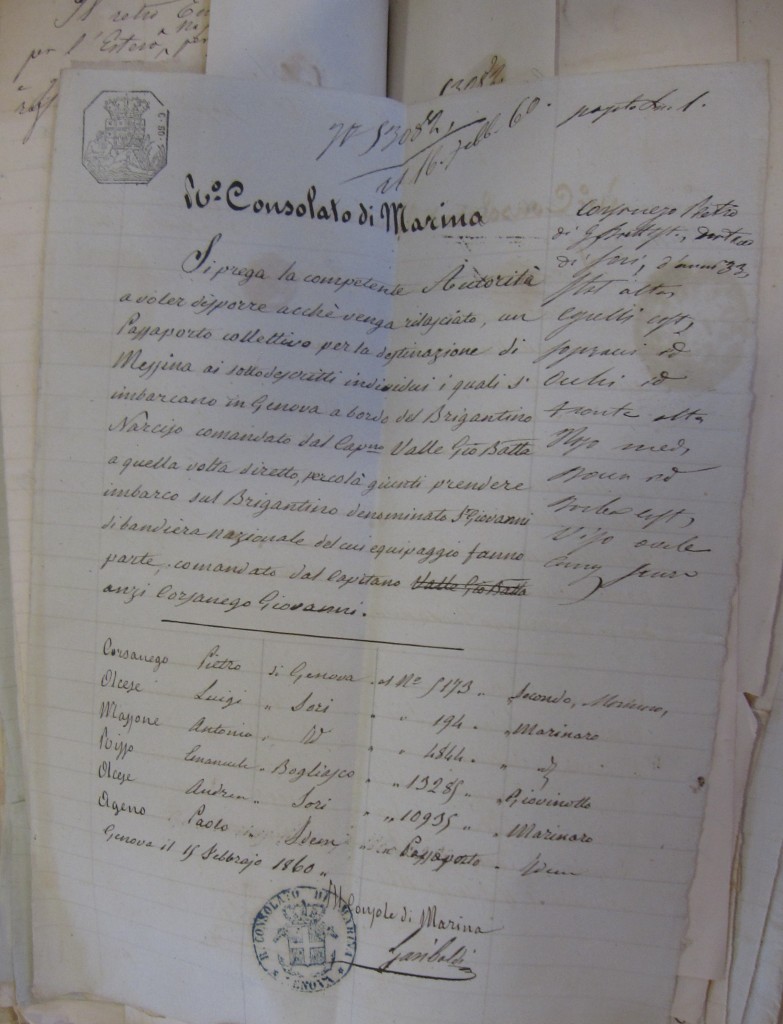

Here is another case of a multiple request to obtain passports: in this case, they were seamen and they needed the document to be able to sail to Messina, where they were going to reach the vessel they were working on.

This is really a document that tells a story!

A passport that was returned to the Questura after the journey: this document actually traveled around the world in his owner’s pocket.

Its folds, its tears, all the stamps and notes tell the story of an adventure!

IS ONLINE RESEARCH POSSIBLE?

After seeing the conditions of these documents, I bet you are all wondering if there is a quick way out: were these documents scanned or indexed?

Last time I went there (March 2024) the staff of the State Archive told me someone is going to scan the documents and put them online. No date knowm, which means that it may take 1 year, 10 years, or perhaps the project will be canceled.

Anyway, a part of these documents (indexed!) is already available online on the following website, even if I am not able to tell which years are included.

I hope you found this article interesting. Leave a comment if you did, and feel free to tell me your experience about old Italian passports.

One thought on “Passports in the 19th century”